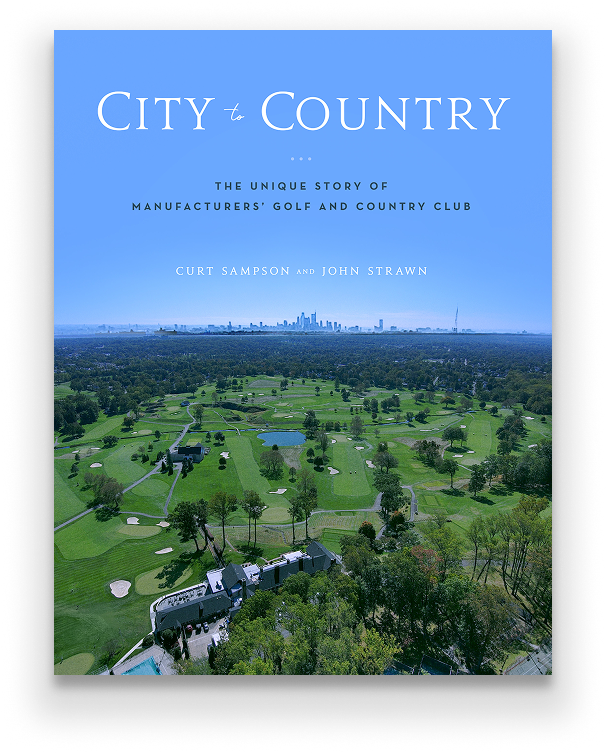

City to Country

The Unique Story of Manufacturer’s Golf and Country Club

Philadelphia’s fabulous collection of William Flynn-designed courses includes Manufacturer’s Golf and Country Club, whose unusual name reflects its origins as a 19th century gathering place for Philadelphia’s ambitious businessmen.

Read More